Vlieland during the war years

Reading time: more than 8 minutes

The mobilisation period, from 1939, was peaceful on Vlieland. Other than a few aircraft flying over, nothing really happened. Even the invasion of the Netherlands by the Germans was hardly noticeable on Vlieland. On 18 May 1940, the Protocol of Surrender was signed. From that day on, the island was governed by the German Wehrmacht.

Parade and inspection of the Dutch troops by the mayor of Vlieland.

The more than 240 Dutch soldiers that had mobilised were able to return home shortly after without ever having fired one shot at the enemy. German occupiers came to the island in large numbers. Vlieland had just 500 residents compared to the occupied forces' nearly 1,000 Germans.

The Atlantic Wall

Just like on the other Wadden islands, the Germans immediately began to build batteries on Vlieland for coastal and air defence. The so-called Flak (abbreviation for ‘Flugabwehrkanone’ or ‘Fliegerabwehrkanone’) artillery was used for air defence. The batteries were part of the Atlantic Wall.

The West-Battery was built in the most westerly dune area of Vlieland, more than 10 kilometres from the village. Within two years, a complex with more than 57 cement and stone buildings and several wooden and corrugated plate constructions arose here.

Flak artillery and the East-Battery.

East-Battery roll call area.

A battery was also built on the eastern side of the island. This Flak battery was situated on the site where, in 1917, the Dutch navy had already built a fortification. The fourteen Dutch buildings were expanded to a total of 56 buildings.

The FuMG 39T radar on the East-Battery. This photo was taken after the liberation and shows men from the Vlielandse Nederlandse Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten (NBS) and English military men.

Occupation

During the occupation, the freedom of the Vlielanders became more and more limited. Groups of more than twenty people were prohibited, as was hanging around on the street unnecessarily. And the lighthouse lantern went out. Access to the beach was limited at first and later completely prohibited.

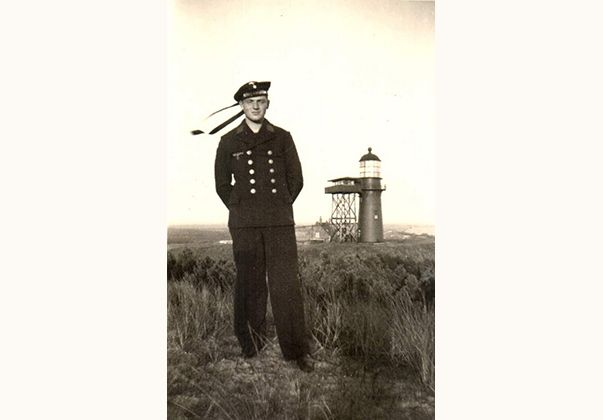

A German seaman poses at the lighthouse. This photo was taken early in the war before the lighthouse was painted in camouflage colours.

German military men were still allowed on the beach for recreation.

To leave the harbour, residents had to report and fishermen had to have a special Ausweis (identification card). The Vlielanders were basically prisoners in their own village. Everyone on the Wadden islands did their best to keep the peace, and Vlieland was no exception. Contact with the Germans was often friendly, says Jannie de Boer-Bakker:

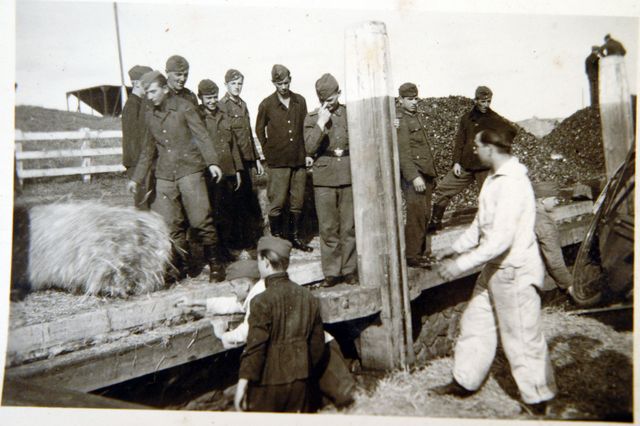

The service harbour was still fully operational during the war. Apart from the fishing boats and dredgers that had to enter the harbour at night, tjalks and containers were also regularly pulled into the harbour by a tugboat. These mainly brought supplies for the occupying forces.

German soldiers unload a merchant ship in the harbour in Vlieland.

Of course, not everything was hunky-dory between the islanders and the occupiers. Johannes de Boer tells about his experience with the Germans:

“[...] Every single time I came rowing in, a German would come to the quay and say: 'Einer für den Kommandant und zwei für mich.’ (One for the commander and two for me) I could never make it to the quay without that man already being there. He was part of the Grüne Polizei and what could I do, I could easily sell that fish in the village. One day I pretended I didn't see him.

“ Du fährst nicht mehr aus dem Hafen aus! (You won't leave the harbour again) ”

There was a skipper on his boat and I started talking to him. I thought to myself 'go to hell'. And suddenly he started to swear. 'Du fährst nicht mehr aus dem Hafen aus!'', he yelled. My Ausweis was taken. 'Now I'm stuck here, dammit', I thought. I couldn't fish any more, I couldn't leave the harbour any more because I couldn't get permission: no Ausweis. I'd made a small boat with a sail from white cotton work shirts: a nice sail, I used linseed oil to make it water resistant. So that was that, I couldn't leave the harbour. That lasted a few days. I had to go to the commander of the Grüne Polizei in 'Golfzang', that's where he was. I had to apologise and then I had to report to someone else in Harlingen. There I had to pay two guilders. [...]”

War at sea

The German and English navy used naval mines intensively to block off parts of the North Sea and their own coast. In storm weather, the mines often broke loose from their anchors and, in the end, washed up on the beaches. And these floating mines could cause a great deal of damage if they bumped into a breakwater or a ferry, with all kinds of consequences.

Also victims of the war at sea and the evacuation at Dunkirk washed up on the beach of Vlieland. These military men were buried in the cemetery on Vlieland.

Graves of French military men who perished in the Battle of Dunkirk and washed ashore.

School children from Vlieland putting flowers on the war graves, around 1950. This was the start of a tradition that continues today.

War in the air

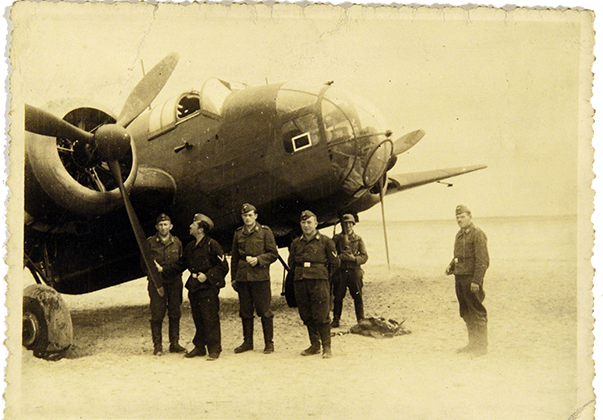

Although the occupiers armed Vlieland with Flak artillery, using it was not always necessary. During the night of 26 to 27 August 1940, 110 aircraft took flight from various airports in England to attack multiple targets in Germany. All these planes had to use navigation systems - still rather inadequate at the beginning of the war - to find their way to their targets. Sometimes crews disappeared. And this was the case with one of these 110 aeroplanes. In the early morning of 27 August 1940, the Hampten P4324 made a perfect landing on the Vliehors using its very last drops of fuel.

The crew was certain that they were somewhere in Scotland. Nothing was further from the truth. Shortly after landing their plane, the crew were taken as prisoners of war by the West-Battery. The plane fell undamaged into German hands and was sent to the Luftwaffe test centre in Rechlin.

During the days that the plane was on the Vliehors, many German soldiers took photos of it.

The air battles were usually much more violent, and the Flak played the leading role. On 22 March 1945, the Stirling LK-209 MA-T took flight on a secret mission. The goal was to drop weapons, ammunition and other supplies for the Dutch resistance. This dropping was meant for the area near Loosdrecht. But it never got that far. During the night of 24 March 1945, the Stirling crashed in the dunes of Vlieland, north of Bomenland. The aircraft was shot at and hit by the East-Battery Flak. Just one of the seven crew members survived the crash.

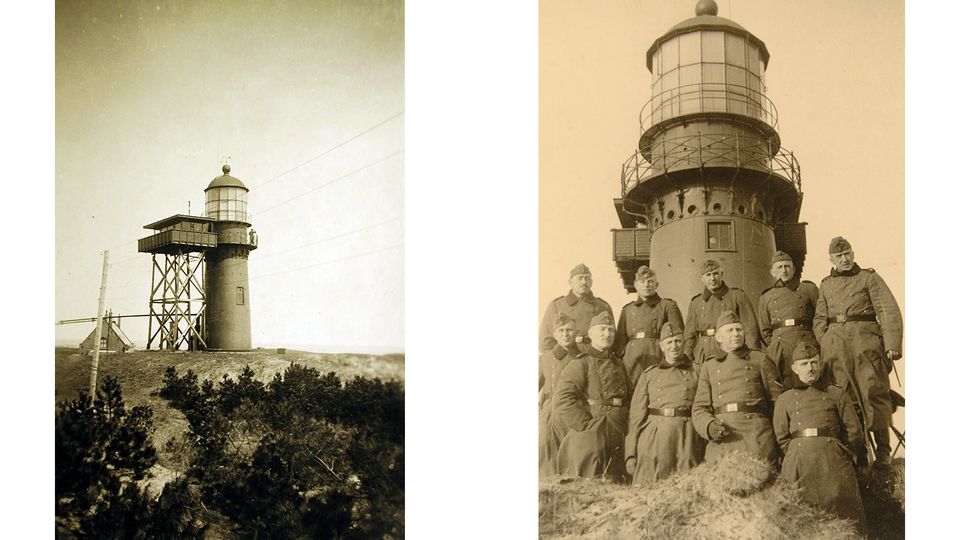

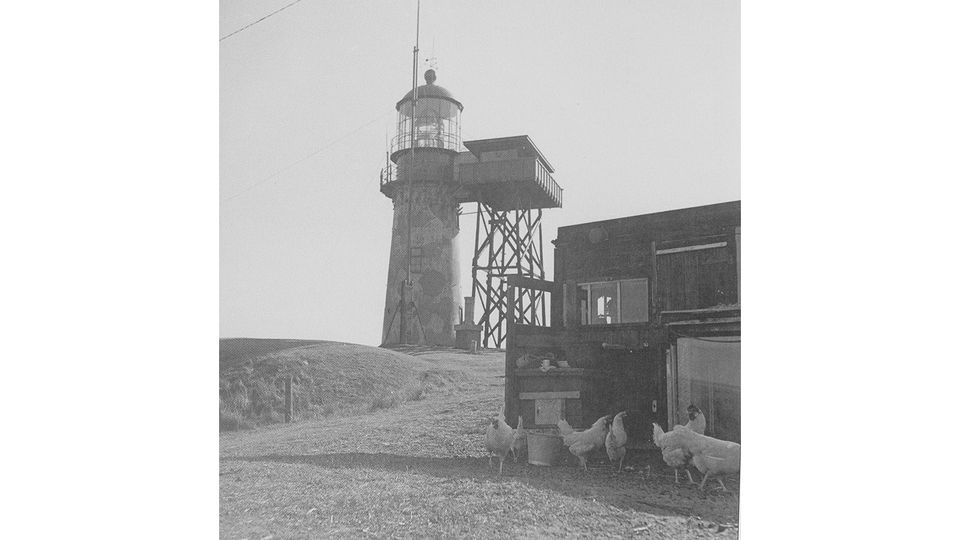

The lighthouse

The lighthouse lantern was extinguished to make things difficult for the Royal Navy. The lantern was only lit when a German convoy passed to the north of the Wadden islands. And then only when the convoy was passing Vlieland.

The occupiers used the lighthouse mainly as an observatory. The characteristic red colour was quickly painted over with the camouflage colours the Germans so often used along the coast.

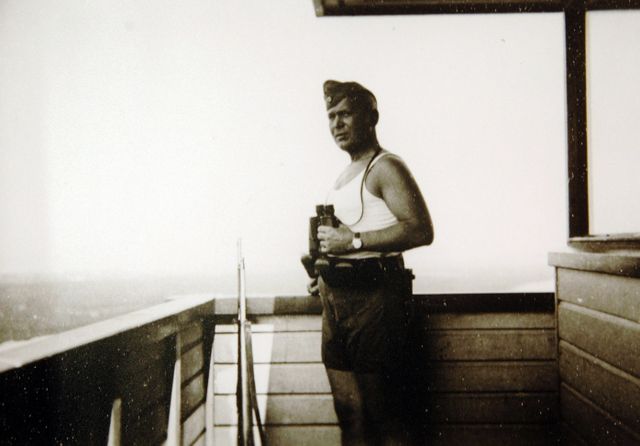

Navy man Wilhelm Dedy on the telephone in the lighthouse lookout.

Wilhelm Dedy in the lookout.

On 4 June 1944, the lighthouse was shot at by allied fighter planes. The cupola and the cap were perforated, 33 outside windows shot to smithereens and almost all the lenses and windows in the lookout room were destroyed.

Lighthouse keeper Klaas Roos looks through a hole in the glass made by the English aircraft attacks.

When the lighthouse keepers were able to return to their lighthouse in1945, they were met with total destruction. But this did not prevent them from lighting the lighthouse shortly after. It was not until 1947 that the lighthouse was painted red again.

The lighthouse still in camouflage colours after the war.

Liberation

When the rest of the Netherlands had already been liberated, the Wadden islands were still under occupation. After the arrival of the 3rd Medium Regiment of the Royal Artillery in Den Helder, they were given orders on 26 May 1945 to send sixty men to disarm the German garrison on the islands of Vlieland, Terschelling and Ameland. This unit was called ‘Jaffa-Force’ and was under the command of Capitan J.D. Johnston.

On 29 May, the Jaffa-Force was moved from Den Oever to Terschelling where the German commander was told that, from that moment on, Captain Johnston was the allied commander of the three islands. On the morning of 31 May, Lieutenant Frederic Squire and five soldiers were sent to Vlieland to ensure the official transfer of power. Vlieland was now finally liberated!

In 1992, Sijmen Kroon told about meeting Squire:

‘I went to the beach in a small motorboat that morning with Juri Kuiper to get some heavy tree trunks. The trunks were fantastic firewood. The Germans had thrown a lot of these tree trunks, about 5 metres long, onto the beach. They were supposed to be obstacles if the allies tried to land.

While we were working, a motor sloop passed by with a few English soldiers in it. We walked along with the boat that moored in the harbour. An English officer stepped off the boat and asked for the BS (Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten) commander. Meanwhile, the BS commander, doctor Robert Turfboer, had arrived and they all went to the village.

The photo shop from Hommema was used as headquarters and Inselkommandant Kapitänleutnant Clementsen was summoned and instructed as to how things would be settled. [...]”

On 11 June 1945, the Germans were brought by ferry to Terschelling and from there the entire occupied forces were brought to Wilhelmshaven.

View of the Vuurtorenduin, June1945. In front of the Nissenhutten, where some of the Wehrmacht infantry units were housed.

Aerial view of Vlieland harbour taken shortly after the war. This is what the harbour looked like during the war, only the buildings at the head of the harbour and the western harbour dam have already disappeared.

Stelling 12H is being restored to be used as a bunker museum. The mess hall bunker will be a restaurant and excursions are already being organised.

Visit Vlieland