No forgotten history

Five conversations about the fascination with WWII

It's been more than 75 years since WWII ended. The number of people who are still able to tell about the war from their own experience is declining rapidly. But fascination for the war years only seems to be increasing. Why is that and what is it that motivates people who have not experienced the war themselves to become so fascinated by it? How do they express their interest? And how important is it that those tales still be told? Five conversations about a history that is still very much alive.

Ties Groenewold has a war museum

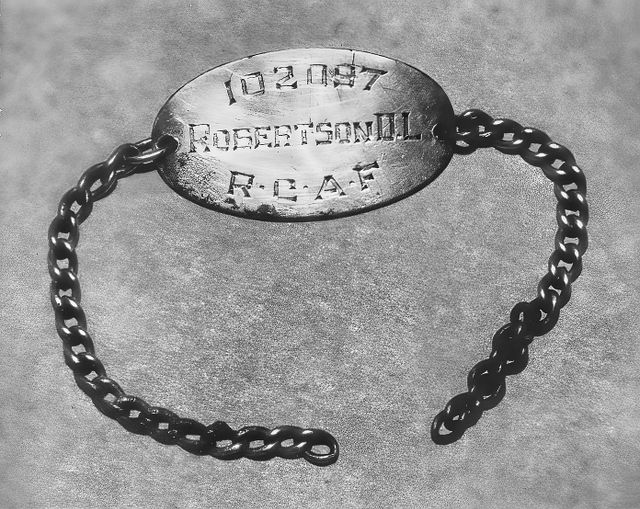

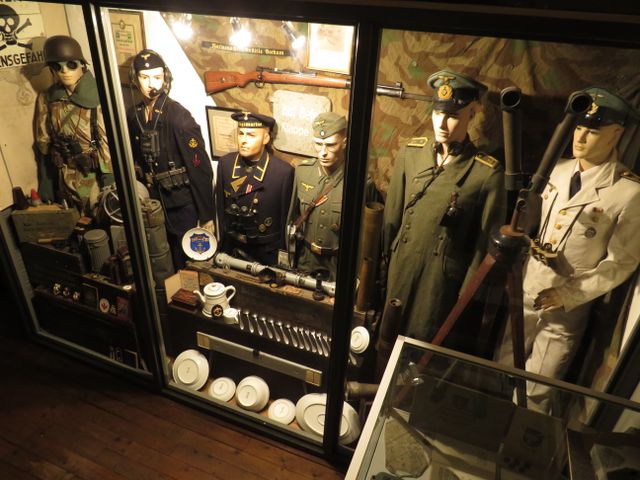

He doesn't really know how it all started. The fascination for World War II and especially with anything that happened in his surroundings during those years has always been there. Ties Groenewold (29) began photographing bunkers more than ten years ago. Soon after, he also started collecting photographs. “Just this week I saw a photo album for sale from an officer who was stationed in Delfzijl. Unique pictures that I want to have, no matter the cost.”

In the meantime, he has gathered so much material that he can always sell something to finance the purchase of things like that photo album. This way, his collection becomes more and more specialised. At the top of his wish list is an album from a soldier who spent part of the war in Middelstum. 93 soldiers were stationed in the village where Groenewold lives and where he created a museum for his collection. He receives between seven and nine hundred visitors every year. The museum is only open a few days a year and you have to make an appointment.

“ Every soldier made an album like that ”

The more than three thousand pictures of Groningen during the war are what makes this collection so special. Groenewold even has two albums from the nearby village of Winsum, but his own village is still missing from the collection. “Every soldier made an album like that. Immediately after the war, many Germans wanted to get rid of this 'rubbish'. But I still often hear about photos being thrown away even today. So, is there still an album from Middelstum out there? This is part of what makes the search so exciting.”

Will his search ever end? Ties Groenewold can only think of one reason why. “If there was a fire or if the collection got stolen, I would not start all over again. This is something you only do once.”

Pieter van den Heede researched WWII games

A history teacher in secondary school piqued his passion for history. And gaming had always been a hobby. After studying history in Ghent, Pieter van den Heede (30) decided to research how games can lead to enriched insights for his masters at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. He already had the idea that they could influence gamers to experience history in a different way. But he wanted to know precisely how. Because WWII is a major theme in games, he decided to focus on that.

What he really noticed was that many games use film imagery. That made him curious. What kind of idea do players get about World War II from a game like Call of Duty? And how can you use that, for example, in schools? “There are games that give a more nuanced image, such as Through the Darkest of Times. In this you, as the gamer, can choose between various roles and you have to make moral choices. That's interesting. Through the Darkest of Times is specifically about the resistance fighters in Nazi Germany”

“ As the gamer, you feel just how vulnerable you are on a battlefield ”

But, according to Van den Heede, even a game that is more stereotypical, such as Call of Duty, can be very relevant in learning more about history. “As the gamer, you feel just how vulnerable you are on a battlefield. That experience can make you view a story, such as the invasion of Normandy, much differently.” A one-sided or distorted image can also be a good way to get a discussion going in a classroom, according to him. “When you see how long certain stereotypes remain, it's good if the youths can learn to recognise and question them.”

Jörgen Boumans makes ‘living history’

While on holiday as a boy, Jörgen Boumans (44) from Limburg met two boys his own age from Brabant. They invited him over. It was the beginning of a close friendship based on a Scouting troupe from Brabant. When they had to leave the scouts at the age of eighteen, they decided to pool the money from their annual fees and continue to do things together. One day, they saw an old military truck for sale.

None of them had a driving license, but they drove the truck home to restore it. “At that time, we had little money and a lot of time,” says Boumans. “We all pitched in to have enough to buy a can of paint.” Through restoring and trading, they expanded their fleet of vehicles. One of their fathers lent them an empty warehouse to use as a garage. “Throughout the years, our interests broadened and the vehicles became larger and heavier.” They bought a half-track and eventually a tank. A German Nashorn, of which only one remained in a Russian museum, and one in an American. “And then one in a farmer's shed in Brabant.”

By then, the group of friends had joined the Landelijk Platform Levende Geschiedenis (National Platform for Living History) so they could attend events with their equipment. They meticulously re-enact the Battle of the Bulge every year, but they are also often asked to participate in other events, usually with a local theme. “There's a lot of history behind all of it. It's always interesting to dig into that.”

The attendance of veterans always makes an event a little more special. But Boumans also likes to perform for children because he thinks it's important that they hear the stories. He also thought the lunch they prepared in a mess tent for a nursing home was pretty special. “You hear so many stories about the things people experienced themselves during the war years, their fears and emotions.”

In 2019, fate struck the group of friends. Right after the first event with the Nashorn, a fire broke out in the garage and destroyed all of the group's equipment. Their initial reaction was to call it quits. But that didn't last long. They are currently putting all of their time and energy - with support from an on-going crowdfunding campaign - into restoring the tank. You can follow the project via the Facebook page ‘Nashorn Restauration’.

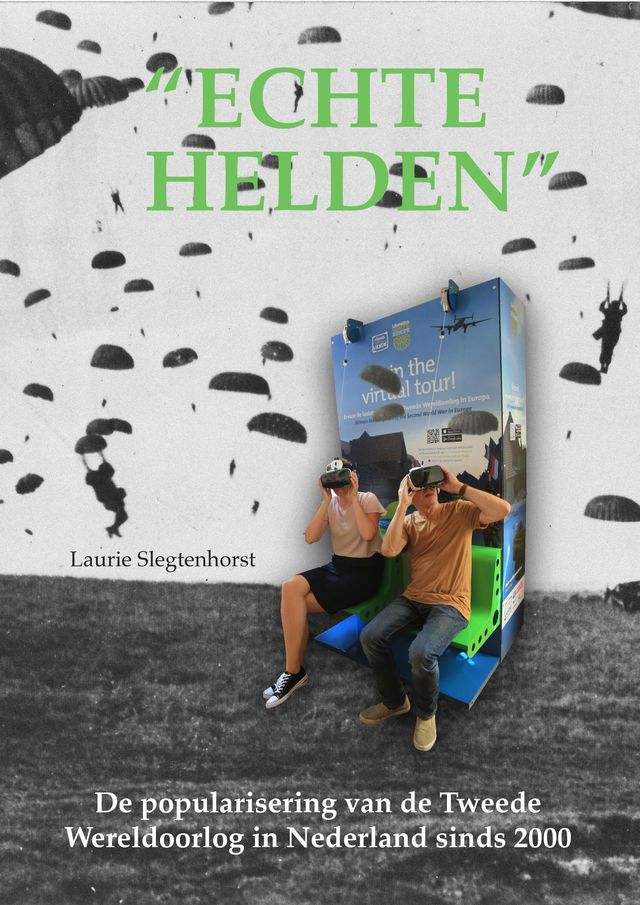

Laurie Slegtenhorst researched how WWII is depicted in popular productions

Her great-uncle died on the Grebbeberg in May 1940. Her grandfather would take her with him to the commemoration every year. She became so interested that she decided to study history with a specialisation in remembrance culture. She volunteered in Buchenwald and spent a year working as a member of the educational staff in Dachau. In 2019, Laurie Slegtenhorst (33) obtained her PhD for her research into the popularisation of World War II in the Netherlands since 2000. Her doctoral thesis is titled ‘Echte Helden’ (True Heroes).

For her research, she explored how popular productions depicted war heroes after 2000. What is the image they depict and how do audiences react to this? To be able to thoroughly analyse the material, she selected three productions from the immense assortment: the musical Soldaat van Oranje, the film Süskind and the Liberation Route Europe, the routes that follows in the tracks of the liberators. For her research, she also studied the education materials that accompanied the productions.

The degree of fiction makes a big difference to how things are perceived. The story is dominant in musicals and films. It must entice the viewer with adventure, love and betrayal. “That makes sense,” according to Slegtenhorst, “but it leaves less room for nuance. Particularly in Soldaat van Oranje, it is right versus wrong. In Süskind, with its ambivalent hero, this is less evident.” But both productions make young people think, especially when the subject is taken up by the teachers in the classroom. “The educational material is very good. For one thing, it poses a lot of questions that require empathy. This makes it possible for young people to relate to the stories.”

“ The most important thing is that the stories are kept alive ”

The Liberation Routes do this a bit more by visiting authentic places. This triggers emotions, and Slegtenhorst witnessed that during the many excursions she took part in. “When you experience first-hand how steep a path is, it becomes much easier to picture how impossible this must have been for the soldiers who had to use it as a supply route,” she gives as an example. “This isn't fiction, this is a 'real' experience.” She also noticed this strongly with American and Canadian soldiers who, during the International Four Day Marches, follow in the footsteps of their predecessors who fought in the Netherlands, as a tribute.

The most important thing for Slegtenhorst is that the stories are kept alive. Popular culture helps this and it's okay that excitement and adventure are part of tit. “You attract more people and it provides a reason to start thinking about history.”

Psychologist Trudy Mooren on the value of commemoration

As a psychologist, Trudy Mooren knows from her practice how important commemoration is. She works at Arq Centrum’45, the national centre for psychotrauma where various organisations that work with the processing of traumatic events, such as wars or attacks, collaborate. Mooren also researches the value of commemoration. “The ritual on 4 May, including the two minutes of silence, still touches people of all generations. It leaves an impression and evokes emotions. People feel connected afterwards.”

Research has taught her that how people experience these days depends greatly on their personal experiences. For people who lived through the war, it can help in processing things. Still, after all these years. “You see them well up, but you know they are in a safe place. Exposure is a way for us to process things. These days can help with that. And the solidarity is tangible. That can also be a support.”

Mooren also did research with children. One of the things she studied is whether there was a difference between children from regions where commemoration is more/less important. “Almost every family has its stories. However, it is more important in regions where schools teach less about World War II that parents share stories and pique their children's curiosity. Of course, there are children who say 'I'm not interested' and that is okay too. But most children do think commemoration is important. They want to be more than just 'the generation that holds a flower'. They want to understand what happened and what is being commemorated.”

World War II is still a very important part of our history. But Mooren notices that other stories are coming to the foreground too, such as slavery and decolonisation. She does not think this will diminish the value people attribute to 4 and 5 May. She thinks the connection between the two days is also important. “The commemoration on 4 May gives more meaning to 5 May. It gives content to the liberation by making people aware that freedom is not evident.”

“ Children want to understand what happened and what is being commemorated ”

The way we commemorate has varied over time and, according to Mooren, it will stay that way. And there will always be discussion about it. Some people feel the commemoration should be more about freedom in general, others feel this waters down the story too much. According to Mooren, it is important for the psychological meaning of it all that everyone can follow their own 'tracks'. Rituals have that power. “They are meaningful to everyone.”

-

Nature and the Atlantic Wall

Nature and the Atlantic Wall

-

Digging into the past

Digging into the past

-

Wonderful encounters

Wonderful encounters