Convoy strikes and Gardeners in the Wadden

The battle for the German maritime convoy routes

The channels off the Dutch coast were of vital importance to the German war industry throughout WWII. Every year, 2 to 3 million tonnes of iron ore from Scandinavia were transported to the harbour in Rotterdam via large and heavily guarded maritime convoys north of the Wadden islands. In 1943, for example, 998 merchant ships carrying a total of 2,119,466 tonnes sailed from Cuxhaven to Rotterdam. Anyone who takes a stroll along the North Sea beaches of the Wadden islands can see that those same convoy routes are still being used today.

The Brits fought day and night, both from the air and at sea, to cut off this vital lifeline from Nazi Germany. They did this with direct air raids on the freighters, by installing mine fields in the shipping lanes and by attacking the convoys with fast and agile assault vessels.

A typical maritime convoy off the Dutch coast, photographed from an escorting ship in the summer of 1942. The loaded freighters sail in the middle and are flanked by escorting Flak ships to protect against air attacks from both sides. (Coll. Helmut Persch)

The air raids started in early 1941, mainly in daytime, with twin-engine Bristol Blenheim bomber-fighters. These relatively slow and vulnerable planes were hardly capable of obtaining results and they suffered heavy losses, both from the Flak and the German fighters. Between March and October 1941, 57 Blenheims (with 171 crew members) were shot down in the Dutch Wadden area while the Blenheim crews only managed to damage or sink 9 ships. These daylight operations were virtually suicide missions.

A Blenheim convoy attack in 1941. While in the background a Blenheim just turns away from the ship it bombed, in the foreground a damaged Blenheim crashes into the sea - marking the watery grave of the three young crew members. This picture was taken from the turret on the hull of a third Blenheim. (Coll. Theo Boiten)

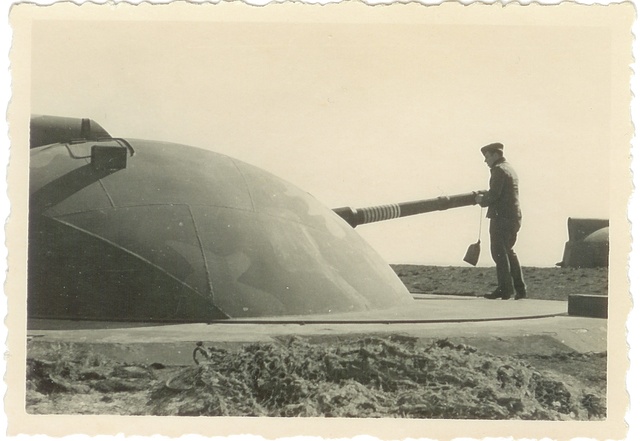

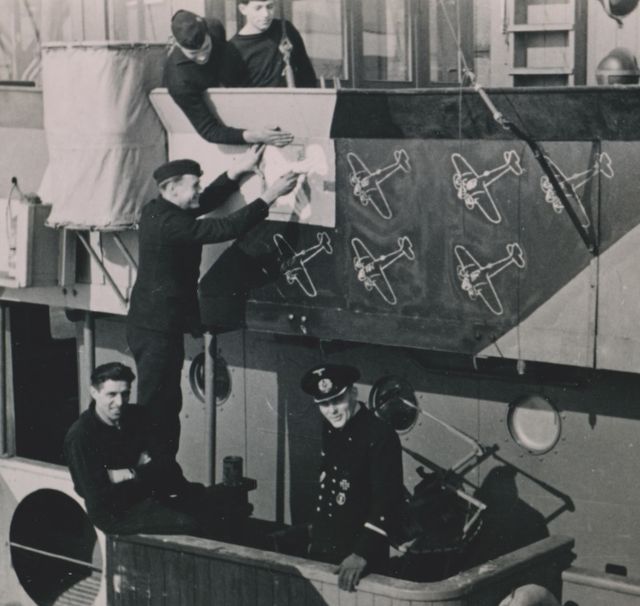

In this way, the German maritime convoy escorting ships kept ‘score’ of the number of British planes they shot down. Here we see the hull of a Vp1304 in the spring of 1942 while the silhouette of a seventh victory has been added. (Coll. Dr. Werner Gast)

A sunken freighter on the convoy route along the Dutch coast. (Coll. Günther Diedrichs)

From November 1941 until the end of the war, the maritime convoy routes along the Wadden islands became the hunting grounds of the Coastal Command of the British air force. Approximately 60 Lockheed Hudson patrol bombers were deployed here up until March 1943. They attacked the German convoys at mast height under the cover of night and bad weather. But this also proved unsuccessful. They sunk 13 ships and damaged an additional 5 in the Wadden area, but it cost them 38 Hudsons and more than 140 crew members. The Canadian 407 Squadron suffered the biggest losses with 18 planes. One of the Canadian airmen who died during a shipping strike (at Den Helder on 20-21 January 1943) was gunner and radio operator Pilot Officer Omer K. Middleton.

Several months prior to his death, he wrote a detailed letter to his sister about a convoy attack in the night of 15 to 16 May 1942 directly above Terschelling:

“During this attack, we were assisted by Hudsons from a Dutch squadron, and they’re no wimps. 9 of our planes took off and at 8:30 a.m. they got into formation and set course for the east. Darkness fell quickly, but the view was unobstructed. The next formation, 3 Canadians and 6 Dutchmen, followed shortly after.

After about two hours of flying, we noticed several explosions to our right. So, we knew that the other formation had found their target and initiated the attack. We approached the battlefield. I thought I'd seen anti-aircraft fire from a German convoy before, but this was something else. While we flew over the coast of Terschelling prior to the attack, we could see planes navigating wildly through the blasts; they looked like crazed bumblebees. They flew very low over the convoy and executed wild evasive manoeuvres until they were out of range of the Flak. We often completely lost sight of planes because of the intensity of the fire.

“ Our planes broke formation and descended on the convoy at full speed, like vultures, straight through the anti-aircraft fire ”

After the first wave of attacks, orange flashes made it clear that the bombs had hit their targets. One ship broke in half and disappeared beneath the waves; another one was set ablaze in no time. A third ship was covered in thick, black smoke. After that, I saw one of our Hudsons spitting out flames before exploding into the waves. Our planes broke formation and descended on the convoy at full speed, like vultures, straight through the anti-aircraft fire. The convoy was a long row of sinister-looking, black ship hulls that contrasted sharply against the sky. The lines of tracer ammunition now came our way, never decreasing in intensity. From my position, I had a perfect view of the other Hudsons executing their attacks. Every aircraft flew just above the water's surface, manoeuvring wildly while hunted by grenades exploding left and right. In the midst of it all, one of our aeroplanes burst into flames while flying over its target and crashed into the sea. Orange explosions appeared behind the planes and the ships were left burning.

“ I thought: This will be the end for us, but we have to push through! ”

I remember subconsciously holding onto things in our plane because the pilot was spiralling the Hudson around in the air. I was fascinated by the spectacle that played out all around me. Imagine enormous fireworks set ablaze, enlarge that to a diameter of 1.5 kilometres and leave it to burn for half an hour. I can hardly even describe it. Green lines of tracer ammunition intertwined with white ones all around us. The sea was wild with exploding grenades and balls of fire hung in the sky like evil eyes. You could see the red muzzle flashes from the heavy calibre artillery as they were firing at you.

Then I had to focus on our target, as we were rapidly approaching it. At the very last second, we saw barrage balloons floating above a burning ship and we made a sharp right. Because of this we were no longer able to guide our bombs to the target, and so we had to turn away and approach the convoy again. I thought: ‘This will be the end for us, but we have to push through!’ During our new approach, a plane, about 50 metres in front of us, suddenly swerved sharply. We thought it was one of our own Hudsons, but when we saw the long, slender hull in front of a burning ship we realised that it was a Messerschmitt 110 night fighter. So our pilot quickly dropped the bombs, went flat out and soared right underneath the 110, making our escape. The Kraut pursued us and fired at us a couple of times, but he couldn’t lock on to us and soon lost us.

We returned to our base safely, one of the two fortunate ones. All the other Hudsons had been severely damaged and some of them had to perform emergency landings. We had suffered heavy losses, more than half of our squadron had perished.”

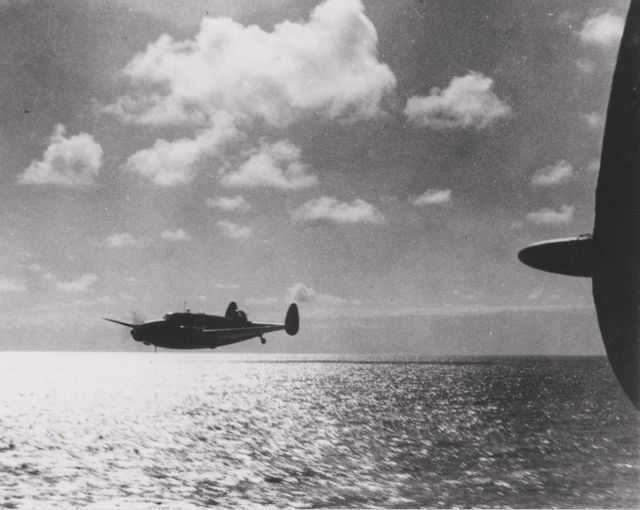

Two Hudsons patrol above the sea at low altitude along the Dutch coast on a clear, moonlit night. (Coll. Kim Abbott)

A freighter carrying iron ore is critically hit by a torpedo and capsizes off the Dutch coast in the summer of 1943. The crew is rowing towards the escort ship, from which this picture was taken. (Coll. Günther Diedrichs)

Not until 1943 would the Brits get a grip on the German convoys. In that year, a new type of fighter plane, the Bristol Beaufighter, was taken into service at the front. With this plane, the tactical concept of the Strike Wing was also introduced. This meant that a large and close formation of Beaufighters would ‘overwhelm’ the convoys with their destructive fire power.

A torpedo Beaufighter with a Mustang escort fighter. (Coll. Harry Alderman)

Wing Commander Hugh Wheeler, a Strike Wing attack leader, explains:

“Our attacks must have been a crushing experience for the German ships' crews. After I had given the attack signal, 3 Beaufighters would dive down onto every escort ship, every one of them carrying 4 bombs, 4 20 mm cannons and 6 machine guns. The Beaufighters frontal fire power was so immense that you got a real rush when speeding towards an enemy ship while it was shooting back with all its might. The escort ships often lost the fight because they had to fight against 3 Beaufighters at once. Once above the ships, we dropped our bombs. When we managed to get a direct hit on a ship’s bridge, as happened to me once, the entire bridge, including the crew, would go overboard.

During the siege on the escort ships, the torpedo Beaufighters would initiate their attack at a low altitude, hoping that we had sufficiently suppressed the escort ships’ anti-aircraft fire. They would then release the torpedo close to the merchant ships, sinking them. The Strike Wings fought one of the grimmest and bloodiest military campaigns of the entire war. Everything happened at low altitude and short range. A typical Beaufighter Wing attack lasted no more than 5 minutes, but those minutes were hell on earth for those involved.”

An iconic picture of a Beaufighter Wing attack. On 25 August 1944, the German minesweeper M347 was attacked and sunk in the Huibert Gat north of Schiermonnikoog. (Coll. Harry Alderman)

The devastating Strike Wing attacks carried out between April 1943 and August 1944 between Borkum and Texel resulted in approximately 38 ships being sunk or heavily damaged and dozens of others suffering substantial damage. From March 1944 on, the Germans would often sail past the Wadden by night because the Strike Wings were unable to carry out their coordinated attacks then. From August 1944, not a single ship would sail through this area by day. But the British victory in the battle for the convoy routes along the Wadden had cost them dearly: 80 Beaufighters were shot down in this area, costing the lives of more than 140 crew members.

From the autumn of 1942, the British navy’s Light Coastal Forces were active by night in the Wadden area. They carried out attacks on the German maritime traffic by night with fast and agile Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) and Motor Gun Boats (MGBs). During the night of 10 to 11 September 1942, the first mission was carried out off the coast of Terschelling, in which the Vp1239 was hit by a torpedo from the MTB234 and had to be towed to the harbour in Terschelling with 13 heavily wounded on board. Between that night and the middle of 1944, several dozen sea battles were fought in the Wadden area, between Texel and Terschelling, in particular. This resulted in 14 German ships being sunk or heavily damaged, but also the loss of 1 MTB and 1 MGB.

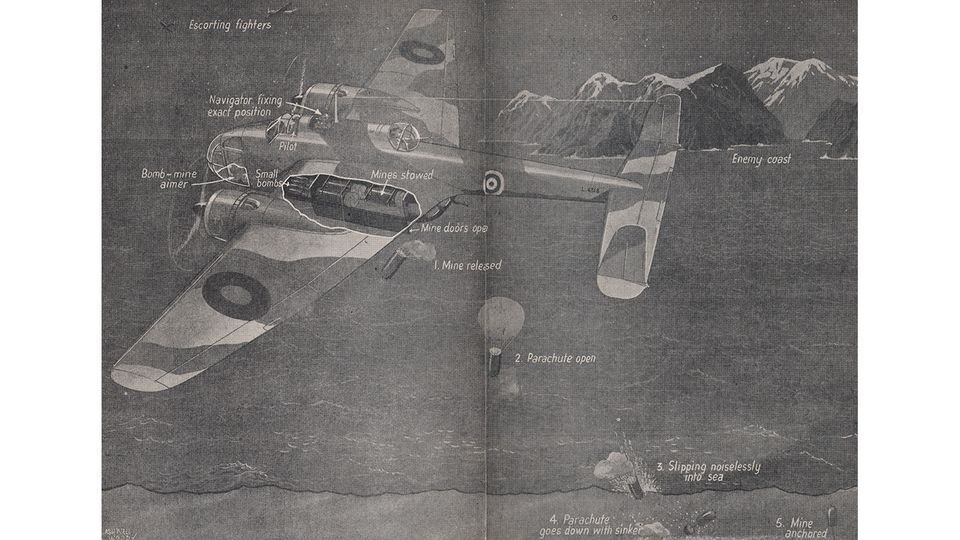

Apart from direct air raids, the battle for the convoy routes was also fought with a ‘silent’ offensive. Almost every night during the war, up to 100 bombers were sent to the Wadden area under the cover of darkness to make the convoy routes unsafe by depositing magnetic naval mines. Laying the mines was done under the codename Gardening. The magnetic mines were ‘planted’ on the German convoy routes. The Brits named the various minefields after shellfish, fruits and flowers, such as Limpets (Den Helder), Trefoils (Texel), Mussels (Vlieland-Terschelling) and Nectarines I (Terschelling-Ameland).

Map of the British minefields in the Dutch Wadden area and their code names. (Coll. Theo Boiten)

Every day, German minesweepers cleared a narrow path in the convoy routes, removing hundreds of mines. The convoys carrying iron ore had to navigate through this path. Despite these sweeping operations, at least 28 ships were sunk by mine explosions in the Dutch Wadden area. Many mines also washed ashore on the islands' beaches and lots of fatal accidents occurred disassembling them. In early January 1943, for example, when an exploding mine on the North Sea beach of Vlieland wiped out an entire German dismantling crew of 14.

The relatively slow and low-flying British minelayers were often an easy target for the German anti-aircraft artillery on the Wadden islands: between 1940 and 1945, the Royal Air Force lost approximately 100 minelaying aeroplanes in this area, causing the deaths of around 500 crew members.

Photo of a German minesweeping operation: behind a minesweeper from the 4th Räumboot Flotille a mine in the British minefield off the coast of Terschelling explodes with a gigantic bang. (Coll. Karl Köster)

On 9 August 1942 ,the 4,528-tonne Swedish freighter ‘Sigyn’ was hit by a mine explosion off the coast of Texel. An attempt was made to tow the heavily damaged ship to the harbour in Den Helder, but this attempt failed. Therefore, it was grounded and sunk before reaching Den Helder. (Coll. Alfons Borgmeier)

There are many stories to be told in the history of ‘Wadden area: front line’. Here are 10 of them:

Suicide by daylight: the Blenheims, 1941

On 15 October 1941, the British daylight anti-shipping campaign carried out a routine operation. 12 Blenheims were sent out to disrupt the maritime traffic along the Wadden islands, 5 of them did not return. A month earlier, Sgt Eric Atkins had joined 139 Squadron as a pilot. On 15 October, he flew his first mission in the Bristol Blenheim:

“We received orders to attack the maritime traffic right above the island of Norderney; this was a 1,000-kilometre round trip from our air base in Norfolk. We were told that there were at least 5 German airports in the area and that the coastline was littered with anti-aircraft artillery. The German maritime traffic was also defended by Flak ships. The forecast predicted bad weather with low-hanging clouds and drizzle for the major part of our flight course. The prospect of continual precision flying at low altitude above the sea - in bad weather - and facing a challenging target on our first mission, was worrisome.

“ I had to keep blinking to stay focused on my altitude ”

Our Squadron consisted of 6 Blenheims, flying in 2 V-formations of 3 planes each. To make sure the enemy radars wouldn’t be able to detect us, we had to fly so low above the water level that sea foam splashing onto my cockpit windows hindered my sight. The clouds and rain made visibility even worse and I noticed that I started to get hypnotised by the waves quickly passing underneath me and the pattern of the clouds right above sea level; I had to keep blinking rapidly to stay focused on my altitude and on the Blenheims flying close to me.

I was completely concentrated on my instruments and the other planes, when all of a sudden, I heard the rattling of machine guns to my right - where no-one was flying. 'What the hell was that?!' I yelled. ‘Sorry skipper,’ Bill said from his gun turret, ‘I was just testing my guns!’ When we approached the designated search area, my group of 3 Blenheims set course for the target, while the other 3 turned towards the adjacent search area. They disappeared from sight and we concentrated on the sea and clouds ahead. We spotted a small ship to our right, this was a ‘snitch’ - a ship that would inform the German ships and fighter planes about our position by radio. Bill laid fire on them as we passed by. We couldn't divert from our course to destroy the ship, so we just had to hope that Bill had damaged the ship enough to prevent them from 'snitching' about our presence.

We adjusted our course a bit to the north of our search area and I thought to myself: ‘This weather sucks, even if we would be able to spot a ship we would only lose it immediately because of the rain and the clouds, and manoeuvring and attacking at such low altitude won’t do any bloody good.’ But at that exact moment, our formation leader shouted over the radio: ‘Attention, two ships dead ahead!’ And there they were, escorted by two Flak ships. We had no time to gain altitude, so we broke formation and each plane initiated an attack.

“ We were so close that I swore I could see the whites of the German gunner’s eyes! ”

I decided to attack one of the ships from behind. I couldn’t see any of the other Blenheims any more. Just when I had locked on to the target and dropped the bombs, my navigator Jock shouted: ‘Watch out for that Blenheim on your left!’ I managed to pull up slightly, allowing the other Blenheim to pass underneath me. Bill said that our bombs had missed the target by a hair and he laid heavy fire on the ship that was now behind us.

When I flew over the enemy ship, it seemed like I was staring straight down the barrel of an Oerlikon cannon that fired at us - we were so close that I swore I could see the whites of the German gunner’s eyes! I remember well that the enemy reacted to our attack in a calm and meticulous manner - no trace of panic, simply a stoic reaction to yet another attack. We made an attempt to turn the plane around and attack once more with our machine guns, but the weather had gotten even worse and we weren’t able to approach the ship in a good way. We just hoped that the machine guns had done quite some damage and the bombs had fallen close enough to the ship to rattle it. Maybe the others had fared better. Our leader called over the radio: ‘Resume formation and return to base.’

All three Blenheims were able to locate each other and, in formation, we set course for home. The plan was for the other formation of 3 planes to join us around this time, but we couldn’t see them. This could simply have been due to the fact that they had flown further east and maybe they had run into quite a lot of trouble too.

But when we'd returned to base, we still hadn’t heard from the other 3. And that's where the story ends - they never returned. All 3 aircraft - and their 9 crew members - were reported as ‘missing in action’. A 50% loss on my very first operational flight really hit me hard. I remember saying: ‘They were even more experienced than us, so what kind of odds does that give us!’ But then again, the first rule of survival is: ‘I came out of it unscathed and I’ll make sure it stays that way!’ The first operational flight was behind us. But the memory of the dramatic fight and the loss of our comrades weighed heavily on us for days to come. We never did find out what happened to them.’

In the bad weather, Eric Atkins’s Blenheim formation had mistakenly flown to the wrong search area; while they thought they had attacked a convoy near Norderney, but they were actually north of Ameland. They caused no mentionable damage. In addition to the 3 Blenheims from the 139 Squadron that all went missing, another 2 Blenheims from the 114 Squadron fell prey to German fighter planes west-northwest of Den Helder. None of the 15 crew members survived; 14 of them are still missing.

A Bristol Blenheim from the 18 Squadron is speeding towards a German convoy just metres above the waves, off the Dutch coast in the summer of 1941. (Coll. Monty Scotney)

This photo vividly illustrates the everyday risks of attacks on German maritime convoys at mast height. On 16 June 1941, Blenheim V6034 from the 21 Squadron lost half its wing when it hit the mast of the ship it was attacking near Borkum. The crew of three died mere seconds after crashing into the North Sea. The pilot Sgt Leavers washed ashore along the Groninger Wadden coast and was buried in Den Andel. (Coll. Jim Langston)

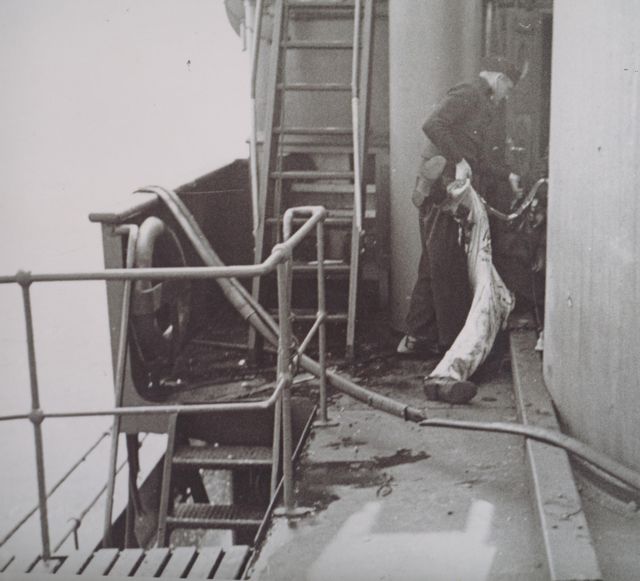

There were many deaths among the crew on the German ships, caused by British aircraft fire. Here we see how the body of a 19-year-old sailor on a Flak ship, who died during an attack on 10 August 1941, is carried into the captain’s cabin. (Coll. Frädrich)

16 September 1941. To avoid detection by the German radars and fighter planes, a formation of Blenheims is flying in formation mere metres above sea level off the coast of Texel. One small steering error could be fatal. A few moments after this photo was taken, the belly of Blenheim V6339 from the 18 Squadron touched the waves and the plane crashed into the sea. The pilot Sgt Tracey later washed ashore on Texel and is buried in Den Burg. His two crew members are stilling missing. The man who took the photo, Sergeant gunner Scotney, remembers: ‘Flights along the Wadden were usually quite long and without protection from fighter planes. For our own safety, we flew at very low altitude during the entire operation, too low for the German radars to detect us, so never more than 10 metres above the sea surface. Even if we didn’t encounter any heavily armed ships to attack, there was always the danger of running into enemy fighters. I was always afraid of encountering the Messerschmitts with their on-board cannons, able to lay fire on us while still out of reach of our machine guns. (Coll. Monty Scotney)

The Australian Wellington and the Ameland lighthouse

On the afternoon of 14 January 1943, after darkness had set in, 7 Wellington bombers from the Australian 466 Squadron flew to the northern coastline of Ameland to drop 2 magnetic mines each into the German shipping route. One of them, the Wellington HE152 flown by Sgt Babington, was hit in the target area by Flak from the 5th and 6th batteries of the Marine Flak Abteilung 246 on Terschelling and crashed into the icy North Sea outside of Ameland at 18 minutes before 6 p.m. All 6 crew members died; one of them, Canadian F/Sgt Stewart, later washed ashore on Vlieland. Today, his 5 comrades are still registered as missing in action. A German military man on Terschelling made a statement that same evening, partially based on which the final victory was contributed to the M. Flak Abt. 246:

“On 14.1.43 at 5:40 p.m. I heard an enemy plane flying in from the southwest and headed northeast. This plane was shot at by the West-Battery, then by a soldier from the Tigerstelling with his gun and after that by the East-Battery. About half a minute after the last shot had been fired, I heard a dull impact about 90 degrees from my position. Then the sound of plane engines died out.”

A pilot from the 466 Squadron, P/O Don Bateman, has a remarkable tale to tell about this mission:

“On 14 January 1943, I received the order to lay down two 1,500-pound mines off the coast of Ameland, near the lighthouse. The weather was terrible, with thick clouds up to about 400 metres above the sea surface. When we arrived at the Frisian Wadden islands, we could barely make out the line of the breakers on the North Sea beach of Ameland. While we were flying around the island, searching for the lighthouse, we were shot at several times and so I decided to fly to the northwestern point of Ameland, then along the breakers to then, after a predetermined number of seconds, turn inland.

Just after we made a turn, a sudden burst of light flashed for about two seconds and during that time I was able to make out the contours of the lighthouse. Aided by this orientation point, I turned directly towards our designated target and dropped the mines in extremely bad weather.

Upon our return to base in England, the entire crew was certain that the lighthouse keeper on Ameland had deliberately risked his life to help us and so we decided to commemorate his deed on the nose of our plane. A bird was painted at an angle under the cockpit, clutching the Ameland lighthouse under its wing. The bird represented a Kookaburra, a species of bird well-known in Australia.”

Illustration from a war propaganda booklet about the Royal Air Force, depicting a Hampden minelayer dropping a mine at low altitude above the sea. (Coll. Theo Boiten)

Nose illustration on the 466 Squadron Wellington of P/O Don Bateman: the Australian Kookaburra with the lighthouse of Ameland clutched underneath its wing. Don Bateman says: ‘The row of bombs next to the Kookaburra represents the number of bomb raids executed by this Wellington. A ‘mushroom’ above a bomb symbolises a Gardening flight - the ‘mushroom’ representing the parachute attached to the mine, which we dropped from an altitude of exactly 230 metres. The first bomb symbol from the left on the top row was the operation on Ameland.”

Strike Wings. The roadstead of Den Helder - the drama of the R131

Because of the stranglehold the British air force and navy had on the convoy routes in the Wadden area, from 1944 onwards the Germans were forced to have more and more of their maritime convoys sail along the Wadden islands to Rotterdam by night. By dawn, the German convoys would then seek safety on the roadstead of Den Helder and continue their journey the following night.

On 21 February 1944, a convoy did not make it to the safety of Den Helder. A British reconnaissance plane spotted a convoy near Texel on its way from Cuxhaven to Rotterdam and a Strike Wing of 36 Beaufighters, escorted by Spitfire fighter planes, followed suit towards Texel. The 13 German ships were attacked at precisely 8:45 a.m. The Beaufighters emerged from low-hanging clouds, raining cannon fire and bombs down on the ships.

The Räumboot (small minesweeper/escort ship) at the front of the convoy was riddled with holes from a 2-cm cannon and then a Beaufighter dropped a bomb from an altitude of about 50 metres. The bomb penetrated the deck and exploded in the ammunition hold. Both the deck and the 2-cm cannon on the stern were blown away by the blast and a fierce and uncontrollable fire erupted on the ship.

2 crew members from the R131 died in the attack and 14 were injured. After 20 minutes, the hold was filled with water and the survivors were transferred to the R103. At 9:10 a.m., the captain Lt. Kurt Fulst and the commander of the 9th Räumflotille Kaptlt. Joachim Fock were the last to abandon the ship, right before the ship’s fuel tanks exploded and the front end of the bow of the R131 finally disappeared under the waves of the North Sea.

Although the British Beaufighter crew also reported a merchant ship in the convoy being left behind severely damaged southwest of Texel, there are no German sources to corroborate this. One of the attacking planes, Beaufighter JM103 from the 143 Squadron, was gunned down near the convoy; a second Beaufighter was so heavily damaged by the German Flak that it was decommissioned upon its return to England.

The Mech. Ogefr. Johann Jenk served as Sperrmixer (mine specialist) on board the R131 and vividly remembers the demise of his ship:

“In January 1944, we came into service of the flottille in Den Helder. First, we did some mine clearance services and then we were ordered to pick up a large Sperrbrecher (minesweeper) south of Helgoland and escort it to Rotterdam, together with a number of other minesweepers. My ship, the R131, was the leading ship on the starboard side of the convoy. One of the ships had engine trouble, so we had to reduce our speed to 15 knots. This meant we wouldn’t be able to reach the safe roadstead of Den Helder before daylight, under the cover of darkness.

“ Me and 3 of my comrades were hurled into the sea and I lost consciousness ”

Suddenly, about 15 nautical miles before reaching Den Helder, approximately 40 bomber-fighters swept down from the clouds and we were under attack. My ship, the R131, was just in front of the rest of the convoy and so we were hit the hardest, the ship was set ablaze in no time. The sole and heel of my left boot were blown off by a 2-cm shell and I fell down onto the deck. Then a British aircraft came at us from the starboard side, firing from all its cannons and dropping a bomb on us, straight into the ammunition hold. This exploded with an enormous bang and turned the poop deck into a sea of fire. Me and 3 of my comrades were hurled into the sea and I lost consciousness. I came to in the icy cold water. I spotted a plank, about 3 to 5 metres in length, that had been blasted out of the port side of our ship, floating not too far away from me. Myself and the Masch. Ogefr. Herbert Schulz managed to reach it and save ourselves.

Meanwhile, the ammunition on board the R131 continued to explode. This made it too dangerous for the other ships to come close to it. It took quite some time before the injured crew members could be saved via the bow.

“ My comrade howled in pain and was crying for his mother ”

A large piece of shrapnel had destroyed my comrade’s knee. I put an improvised tourniquet around his thigh. My comrade howled in pain and was crying for his mother. First, I tried to calm him down with soothing words, hoping to prevent him from going into shock. But that didn’t help. So I pulled my knife and screamed at him that I would kill him if he didn’t start acting like a real German sailor. He calmed down a bit then, probably out of sheer terror.

After the British attackers had disappeared, the R88 approached us and tried to pull us out of the water. While the R88 came at us at high speed, I shouted at Herbert Schulz: ‘Let go of the plank and swim away!’ My limp left foot trailed behind me. Right before the bow of the R88 had reached my plank, I jumped up and grabbed hold of the bow’s edge and propped my right foot onto a bumper. If I hadn’t managed to do that, I would have been run over and torn to shreds by the propeller of the Voith-Schneider engine. However, I didn’t succeed in hoisting myself onto the ship. So, they put a rubber boat in the water and I let myself fall backwards onto it. I still had the broken mast and the flag from the R131 with me and before I climbed on board the R88, I handed them over to ObStrm. Mottinger.

The wounds on my thigh and foot were bandaged and, soaked as I was, I was wrapped in blankets and laid down on the chart table. Only then did I lose my nerves and I started to tremble all over. Comrades from the R88 gave me two mugs of tea with rum to drink (one part tea and three parts rum). This sped up my recovery process; soon I was telling dirty jokes while smoking cigarettes.

When we had reached the harbour doctor’s practice, I asked them to remove my wet clothes. I was then wrapped in warm blankets and transported to the Heiloo hospital near Alkmaar. In total, 50 people were injured during the attack on 21 February. My friend Schulz’s left leg was amputated above the knee on 23 February.”

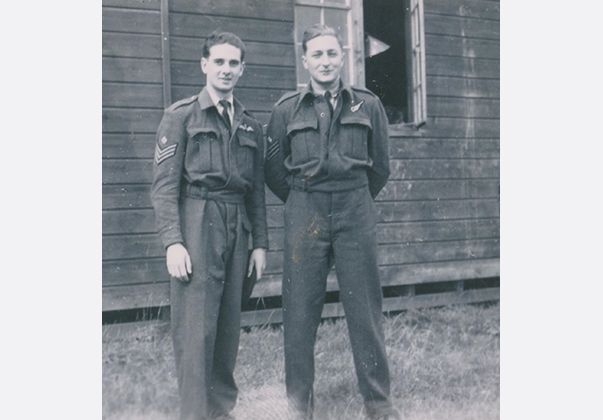

From left to right: F/Sgt Caron (pilot) and his navigator/radio man F/Sgt. Pollard. These two French flying men were shot by German maritime Flak in 143 Squadron Beaufighter JM109 during the strike on 21 February 1944. Caron carried out a successful emergency landing on the sea right next to the German convoy, after which one of the crew members managed to climb into a rubber boat. After that, nothing was heard from the two Frenchmen; they are currently still missing in action. (Coll. Art Edwards)

Immediately after the Strike Wing attack on 21 February 1944, a Räumboot approached the front of the R131, which was engulfed in thick black smoke, to save the survivors. (Coll. Theo Boiten)

Mech. Ogefr. Johann Jenk, Sperrmixer in the crew of the R131, who was injured but survived the demise of his Räumboot on 21 February 1944. (Coll. Johann Jenk)

MTBs and MGBs - the sea battle near Ameland

During the night of 30 September to 1 October 1942, 9 British MTBs and MGBs, led by Lt. Peter G.C. Dickens DSO, coming from the land side north of Ameland, carried out a surprise attack on a German maritime convoy sailing west. The convoy consisted of 8 merchant ships escorted by 5 armed trawlers from the 13th and 20th Vorposten Flottillen. According to the Germans, 5 attackers were sunk and 2 others heavily damaged during the sea battle. Certain is that Lt. Smythe's MGB18 was severely damaged by the fire from the Vp2003 or the Vp1300, resulting in a collision with the MGB82. Lt. Smythe then decided to set his ship on fire - preventing the Germans from seizing it - and abandon ship together with his crew. A grenade impact on the bridge of another MGB instantly killed that ship’s commander. Rating Joseph Metcalfe, who had served as Vickers gunner on board the MGB18 since September 1941, recalls the demise of his ship:

“MGB18 was built by the British Power Boat Company, was 70-feet long and powered by three 1,300 hp Packard gasoline engines with three propellers and three rudders. She was armed with two Lewis .303 machine guns - one on each side of the bridge - and a gun turret above the engine room containing a double .5-inch Vickers machine gun. A 20-mm Oerlikon was installed on the poop deck with depth charges on both sides. The crew consisted of 2 officers and 8 sailors. We were a merry and efficient team and I felt honoured to be part of it.

Together with MTBs, we were sent out to attack maritime convoys, most often successfully. Our ‘working area’ was the Frisian Wadden islands, IJmuiden, Texel and Terschelling. We also performed offensive ‘sweeps’ along the enemy coast, but without the company of the MTBs. Usually, there would be four MGBs and we would attack any enemy vessel we spotted. It got dull and monotonous at times because we often didn’t encounter any ships. But when we did find enemies, we acted fast and furiously. My job as the turret gunner was to lay fire on the enemy with the .5-inch artillery after our captain had gotten us within shooting range.

This time our assignment was to attack a small convoy of freighters. We rendezvoused with the MTBs to go over the strategy. They then sailed off to position themselves between the coast of the Wadden islands and the convoy. At the agreed upon time, we charged at full speed with five MGBs to distract the German escort ships and to keep them occupied while the MTBs torpedoed the freighters - resulting in success.

Escort ship Vp2003 and German freighter ‘Thule’ were both sunk by torpedoes, causing the deaths of 21 men - half the crew - on the Vp2003. None of them have a known grave. Only 1 sailor aboard the ‘Thule’ survived; 10 crew members are still missing.

Joseph Metcalfe continues his story:

“We attacked the escort at short range, losing nine or ten feet of our ship’s forepart in the process; I don’t know if this happened because we were rammed or because of a grenade blast, because I was too busy shooting at the enemy to notice. We realised immediately that we had to abandon the MGB18. We didn't panic, we were a very efficient and experienced crew that could handle any situation. Everyone calmly did what they had to do to prepare for the total destruction of our ship. Our crippled ship was just floating around for a while until Lt. Peter Dickens came alongside us with his MTB and took us on board, while being shot at himself. Our captain, Lt. Smythe, went below deck, broke the gas line and lit it on fire; then he was the last to leave the ship. Fortunately, we didn’t lose any lives.”

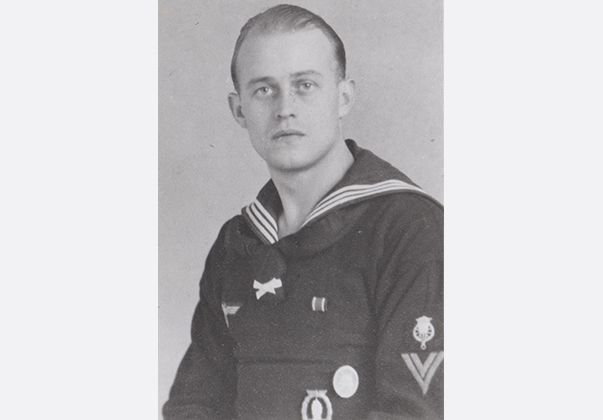

Rating Joseph Metcalfe, Vickers .5-inch turret gunner in the MGB18. This photo was taken two weeks before the MGB18 was sunk during the night of 30 September to 1 October 1943 off the coast of Ameland. (Coll. Joseph Metcalfe)

One of the people who can recount the sea battle near Ameland from the German perspective is sailor Bernard Torzynski. That night, he was on his first mission as cannoneer on the Vp1313:

“At the end of September, we sailed our brand-new ship to Cuxhaven, where a convoy would be assembled to set course for Rotterdam on the morning of 30 September. Our position in the convoy was at the rear right. I operated the 8.8-cm cannon at the front of the ship. We didn't have any steel plate covering; the cannon was wide open. Shortly before midnight, we heard the sound of plane engines, and soon parachute flares were dropped above our convoy. And then the ‘fireworks’ began. We fired flares ourselves to be able to see the enemy. I heard an explosion to the left of our ship; later I was told that a ship from the 20e Vorposten Flotille had been sunk. The freighter ‘Thule’ was also on our left. Earlier that day, I had seen that there were 2 women on board that ship. Our helmsman, Steuermannsmaat Erwin Baumgardt, evaded, without receiving orders to do so, two torpedoes. Had he not done this on his own initiative, the 1313’s maiden voyage would have ended on the bottom of the North Sea. Nonetheless, our steersman was later officially reprimanded by our captain, Oberleutnant Egon Tellgmann, for handling without orders.

“ I heard one of the gun layers shout: Load the cannon, load it! ”

I can’t remember whether our five-man artillery crew was wounded by enemy fire first and the ‘Thule’ was torpedoed afterwards, or if it was the other way around. Whichever it was, the ‘Thule’ broke in two - only 1 man survived by clinging to the mast. After all, 5 of us were wounded, there were only 2 crew members left to perform some of the combat tasks, 1 gun layer and the leader of the artillery crew. The latter dragged the wounded second gun layer from his chair and took over that man’s task. At that exact moment, a British MGB sped by in front of our bow. I heard one of the gun layers shout: ‘Load the cannon, load it!’, but none of us was able to do that because 4 crew members were severely injured. I'd been shot in the left shoulder, but I could still stand up. I can’t for the life of me remember whether it was fear or bravery that drove me, but I got up, grabbed an 8.8-cm shell, pushed it into the gun barrel and yelled at my leader: ‘Loaded!’ I saw the shell hit the MGB with my own eyes.

Two days later, my commanding officer was talking on the radio show ‘Messages from the Front’ and mentioned my name. I was proud of course, but now I'm relieved that the crew of the British vessel was saved; no one wants to lose their father or son.

An MTB launches both torpedoes at full speed. (Coll. Theo Boiten)

Oil painting depicting the nightly sea battle near Ameland during the night of 30 September to 1 October 1942. The two gun turrets on the front deck of escort ship Vp1313 fire at the MGB18 at short range, while the 2,533 tonne freighter ‘Thule’, carrying iron ore, is hit mid-ship by a torpedo. (Coll. Bernard Torzynski)